This is the seventh in a series of articles that will highlight contributions of Milwaukee-area industry to the war effort during the World War II. Many thousands of Milwaukeeans, men and women, helped to provide the munitions to make Victory possible.

During WWII, Milwaukee industry provided significant support for the US Navy, as well as that of our Allies. This chapter includes the contributions of Froemming Brothers, Falk, Cutler-Hammer Louis Allis, and DESCO in meeting the needs of the Navy.

Milwaukee once had a thriving shipbuilding industry. During the days of the wooden-hulled ships, more ships were built in Milwaukee than in any other spot on the Great Lakes. The first vessel built in the city was the schooner Solomon Juneau, built for Milwaukee’s first mayor and launched in August 1837. James Monroe Jones established the first shipyard in Milwaukee and soon moved it to the mouth of the Milwaukee River to an island that now bears his name—Jones Island.

William H. Wolf, however, established the City’s most formable early shipyard. Wolf was born in Germany and came to Milwaukee in 1849. He worked for a time in James Monroe Jones’s shipyard as foreman. Wolf established his own firm in 1858 with partner Theodore Lawrence. The partners sold the company to Ellsworth and Davidson in 1863 but, in 1868, Wolf returned to Milwaukee and bought out Ellsworth to go into partnership with Thomas Davidson. Davidson had also worked for a time in Jones’s shipyard.

Their company occupied eleven acres with one stationary dock and nine floating docks serviced with a large steam derrick. Wolf and Davidson built a number of sailing vessels, including the schooner Moonlight—the largest constructed in Milwaukee at the time at 777 gross tons. However, the company became most known for its wooden steamboats—the largest of which was the Ferdinand Schlesinger which measured 2,607 gross tons with a keel length of 306 feet.

As shipbuilding moved away from wooden hulls and toward larger vessels of iron plate and eventually steel, Milwaukee’s wooden shipbuilders were no longer able to meet the market demands. Shipbuilders in the Lake Erie ports were closer to the Pittsburgh steel district. There were notable exceptions; during First World War, thirteen boats were launched in Milwaukee by Fabricated Ship, a subsidiary of Lakeside Bridge and Steel, and four wooden submarine chasers were built by the Great Lakes Boat Company. And during the Second World War, Froemming Brothers established a shipyard in Bay View.

Froemming Brothers was founded in 1919 by Ben Froemming and his brothers Walter and Herbert. Ben, who was born Bernhard Arthur Froemming, started the firm to specialize in city sidewalk replacement and similar masonry jobs. He was only eighteen at the time, but the small firm’s construction expertise grew quickly. By the early 1940s, the company had grown into an engineering construction company, building roads in Texas, bridges in Pennsylvania and Mississippi, a new airport for the Panama Canal project, and various tunnels in the Midwest.

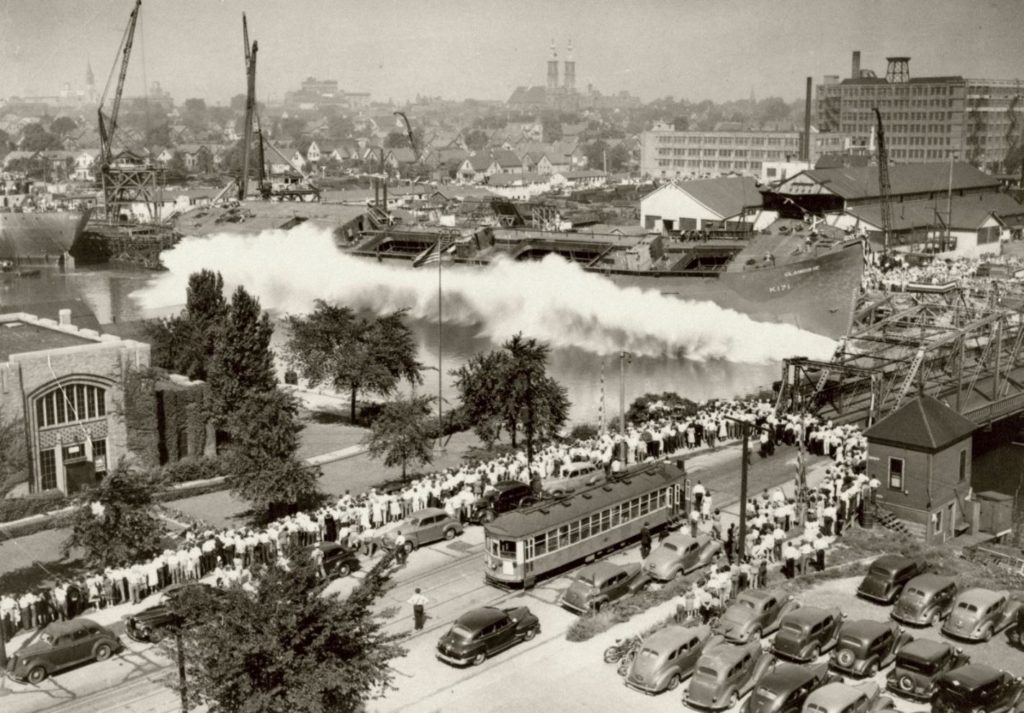

In 1941, Ben Froemming answered an appeal from Milwaukee’s mayor Carl Zeidler to bring back shipbuilding to the City. While the firm had no shipbuilding experience, it bid for and obtained millions of dollars of contracts from the United States Maritime Commission. To establish its shipyard, the company acquired twelve acres along the Kinnickinnic River, just north of Beecher Street and 1st Street. The shipyard was readied for operation in sixty days. The initial order was for eight seagoing tugs, the first of which was launched on July 21, 1942.

Wisconsin Governor Julius Heil attended the launch ceremony and told the guests, “Ben Froemming didn’t have to build ships to make a living, but he is building them because his country needs them. He had the guts to go ahead and build a shipyard even when they told him it was impossible.”

All eight tugs were completed by 1943. Each displaced 1,117 gross tons and was 194 feet long.

While the tugs were still under construction, the company was given a contract to build four anti-submarine frigates. Named Allentown, Bath, Machias, and Sandusky, the frigates were completed in 1943 and 1944. Each displaced 1,430 tons and measured 304 feet in length. They were armed with three 3-inch guns, four 40-mm anti-aircraft guns, and four depth charge throwers.

Froemming received one more contract during the war—this one for 14 cargo ships. These “Alamosa-class” cargo ships were designed by the Maritime Administration and were intended for rapid construction. They were 339 feet in length with a fifty-foot beam and were powered by single Nordberg diesel engines rated at 1,750 horsepower. The last ship under this contract was launched on November 1, 1945. All were named after counties that started with the letter ‘C’ in the United States: The USS Claiborne, Chicot, Clarion, Chatham, Codington, Charlevoix, Craighead, and the Colquitt. Most had only brief service during the war, which ended on September 2, 1945. However, the USS Charlevoix provided aviation fuel for the New Zealand Air Force based on New Britain, supporting their twice-daily raids on the Japanese.

Most of the cargo ships saw service following the war. As an example, the USS Colquitt (AK-174) was transferred to the US Coast Guard, where she was renamed the USCGC Kukui (WAK-186). She was sold to the Republic of the Philippines in 1972 and delisted by their navy in 2001. The USS Clarion was sold to Norway after the war and operated until 1970 when she was wrecked off the coast of Peru.

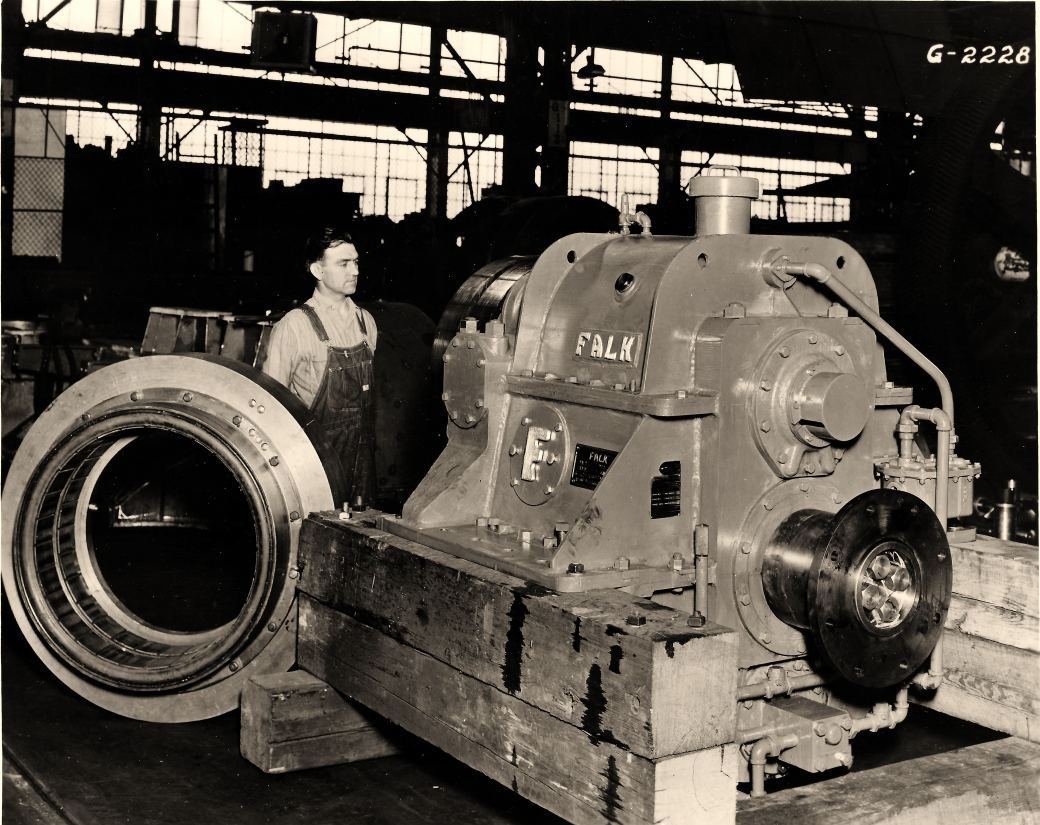

The United States worked to increase the Navy’s arsenal in the years leading up to World War Two by building a number of warships. In order to increase their range and speed, the new warships used steam turbines, rather than less efficient steam engines. Gear drives needed to be installed to allow the steam turbines to match the much lower speed required by the propellers. Milwaukee’s Falk Corporation provided many of these gear drives.

Falk received orders in 1934 for gear drives for the aircraft carrier Ranger, and over the next few years for the carriers, Yorktown, Enterprise, Wasp, and Hornet. During this time, Falk also supplied gear drives for fifteen cruisers and twenty-eight destroyers. But this military business was nothing compared to the demand that occurred following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Falk had already begun to expand capacity—adding a shop in the space between Shops 1 and 2 and expanding its weld shop and foundry. Following the United States’ direct entry into the war, Falk added Shop 4, known as “the Navy building,” to help meet the demand for gear drives for warships. All told, Falk gear drives turned the propellers on twelve aircraft carriers, twenty-seven heavy cruisers, 184 destroyers, hundreds of cargo ships and tugboats, and 1,024 Landing Ship-Tanks (known as LSTs).

The design and manufacturing of the gear drives for the LSTs was a herculean effort. As the Allies began planning to retake France, it became evident that they would need a huge fleet of landing craft to convey troops and supplies into areas without harbors. The landing craft was designed to meet the specific requirements for the amphibious landings. The design requirements for the gear reducers for the LSTs were particularly important. The ships needed to land on beaches, off-load equipment and personnel, and then quickly withdraw from the beach, requiring that the gear reducers be able to quickly move from forward to reverse mode.

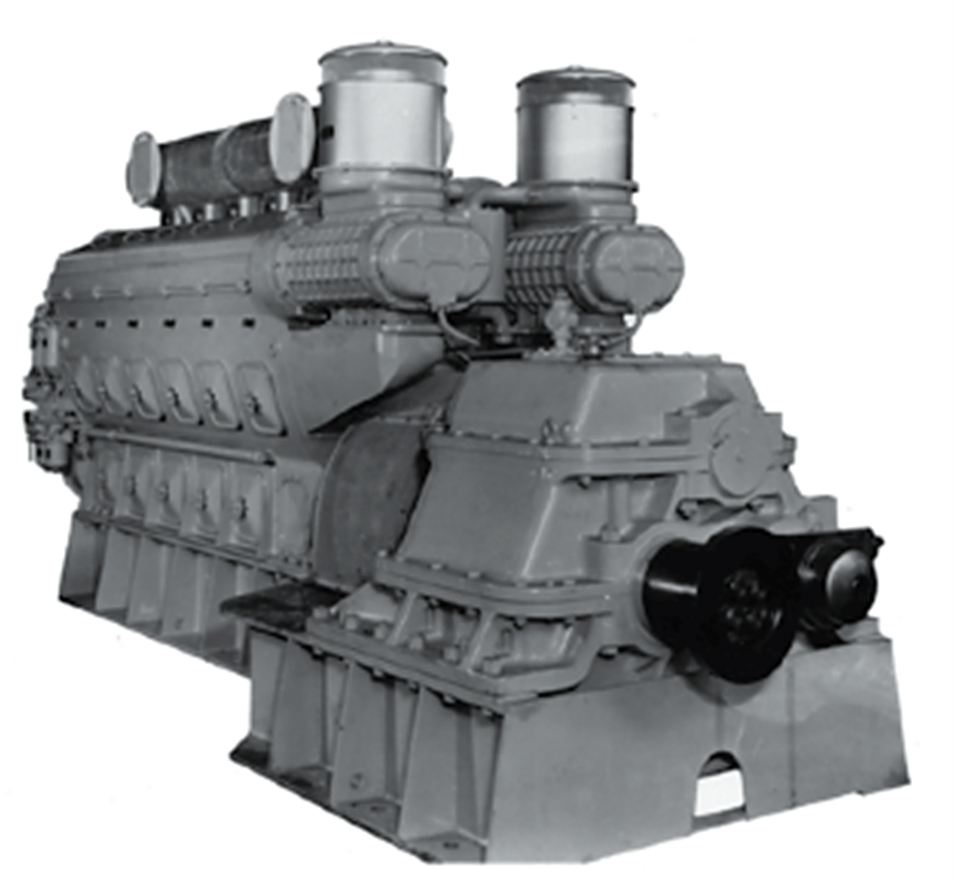

Falk had gained prior experience with reverse gear drives when it designed gear reducers with pneumatic clutches for the diesel-powered Bull Calf—a towboat used on the Mississippi River. Because of this experience, Falk was selected to provide the gear drives and clutches for the LSTs. Falk engineers, overseen by its chief engineer Walter Schmitter, designed a propulsion reversing reduction drive to meet the requirements. A pilot model was rushed into production and performed well—no design changes were required for the production gear drives.

The LST gear reducers needed to reduce the shaft speed of the twin General Electric V-12 diesel engines that powered the propellers, allow both a forward and a reverse drive direction and also provide a means to disconnect the drive from the engines. The Falk drives were designed to handle nine-hundred horsepower at 744-RPM full engine speed.

A key element in the LST gear reducers was Falk’s Airflex clutch, patented by engineer Thomas L. Fawick. Fawick was one of the incorporators of Twin Disc Clutch Company in Racine Wisconsin. He sold his interest in Twin Disc in 1936 and organized the Fawick Clutch Company, which he moved to Cleveland in 1942. Joining forces with the General Tire and Rubber Co. of Akron, he designed a clutch with an inflatable rubber tube molded inside a steel drum that, when pressurized, locked to the main pinion shaft and produced forward motion. When unpressurized, the engine’s power was diverted through a set of reversing gears. The clutch enabled the LSTs to change the propeller direction in seconds.

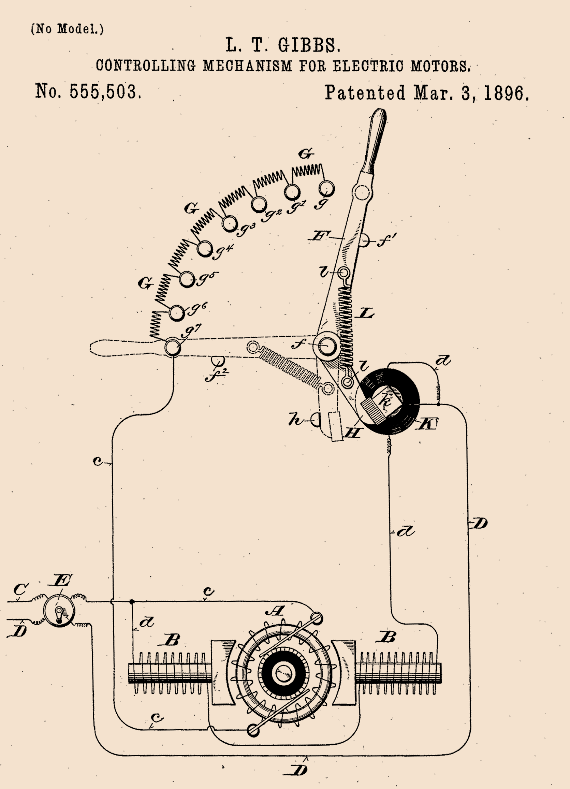

Frank Rogers Bacon was a student at Princeton in 1892 when his mother’s death caused him to return to Milwaukee to work in his father’s grain business, the E.P. Bacon Co. Frank observed the need for electrical equipment and, in 1896, he and an inventor named Lucius Gibbs formed a company named the American Rheostat Company. Their initial product was an electric motor starter that had been recently patented by Gibbs.

While there was an immediate demand for American Rheostat’s new motor starter, their initial design had a number of glitches that needed to be resolved. Gibbs quickly lost interest and sold his stake in the concern to Bacon. Frank Bacon was able to find another partner, Frederick L. Pierce, who provided needed financial backing to get the new product established.

When the improved motor starter entered the market, Bacon discovered another problem. American Rheostat’s starting box was similar to one manufactured by Cutler-Hammer Manufacturing Company in Chicago. Cutler-Hammer had been formed in 1893, specializing in electric starters, speed regulators, and field rheostats, and had introduced an electric motor starter box designed and patented by Harry H. Blades of Detroit. Cutler-Hammer’s new product achieved almost instant success.

Soon, Frank Bacon filed a lawsuit against Cutler-Hammer, claiming patent infringement. Cutler-Hammer countersued. A messy and lengthy legal battle faced both companies. In mid-1897, Bacon approached Harry H. Cutler with a deal to end the lawsuit. They reached an arrangement under which American Rheostat bought out Cutler-Hammer, its plant, and all rights to its patents—but retained the Cutler-Hammer name. Bacon became president of the newly merged company, and Cutler was named plant manager and chief engineer. Operations were initially established in Chicago but moved to Milwaukee in 1899 where facilities for expansion were considered better. The original Milwaukee plant was located on the first two floors of the Badger State Shoe Company at the corner of 12th Street and St. Paul Avenue, just north of the Menomonee River. This location was used by the company until 1975.

The newly merged company quickly went to work at developing other electrical control devices, including crane controls, motor controllers for metal plants and for continuous rolling mills, and motor controls for use on ships. They also developed switches for more mundane applications such as for lamp sockets (for light bulbs), as well as circuit breakers for some of the most demanding medium-voltage electrical applications.

Henry H. Cutler, who continued to be associated with Cutler-Hammer until 1915 as chief engineer and vice president, invented motor starters of numerous configurations, resulting in dozens of patents.

In 1901, the company designed and manufactured the control equipment for the Panama Canal. It also provided the controls for the steam shovels built by Bucyrus-Erie of South Milwaukee, used on the project.

When the USS Indiana was reconstructed in 1904, Cutler-Hammer was invited to design the controls for the ship’s artillery. The power for moving the gun turrets was changed from steam to electric motor drives. Electric drives were also installed to hoist the ammunition and fire the guns. Following renovations, the Navy conducted a test with the new controls. During the first day of trials, the USS Indiana recorded 10 hits in 10 minutes on a moving target. Based on the results of the tests, the Navy decided to implement similar controls for other ships—and Cutler-Hammer marine controls were favored. Since the 1904 trials, one hundred percent of the ships in the US Navy fleet has used Cutler-Hammer equipment.

Almost immediately after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Frank Bacon sent a telegram to the Navy Department. In it, he offered Cutler-Hammer’s entire capacity toward the war effort, pledging to cease the production of commercial products if the Navy so desired.

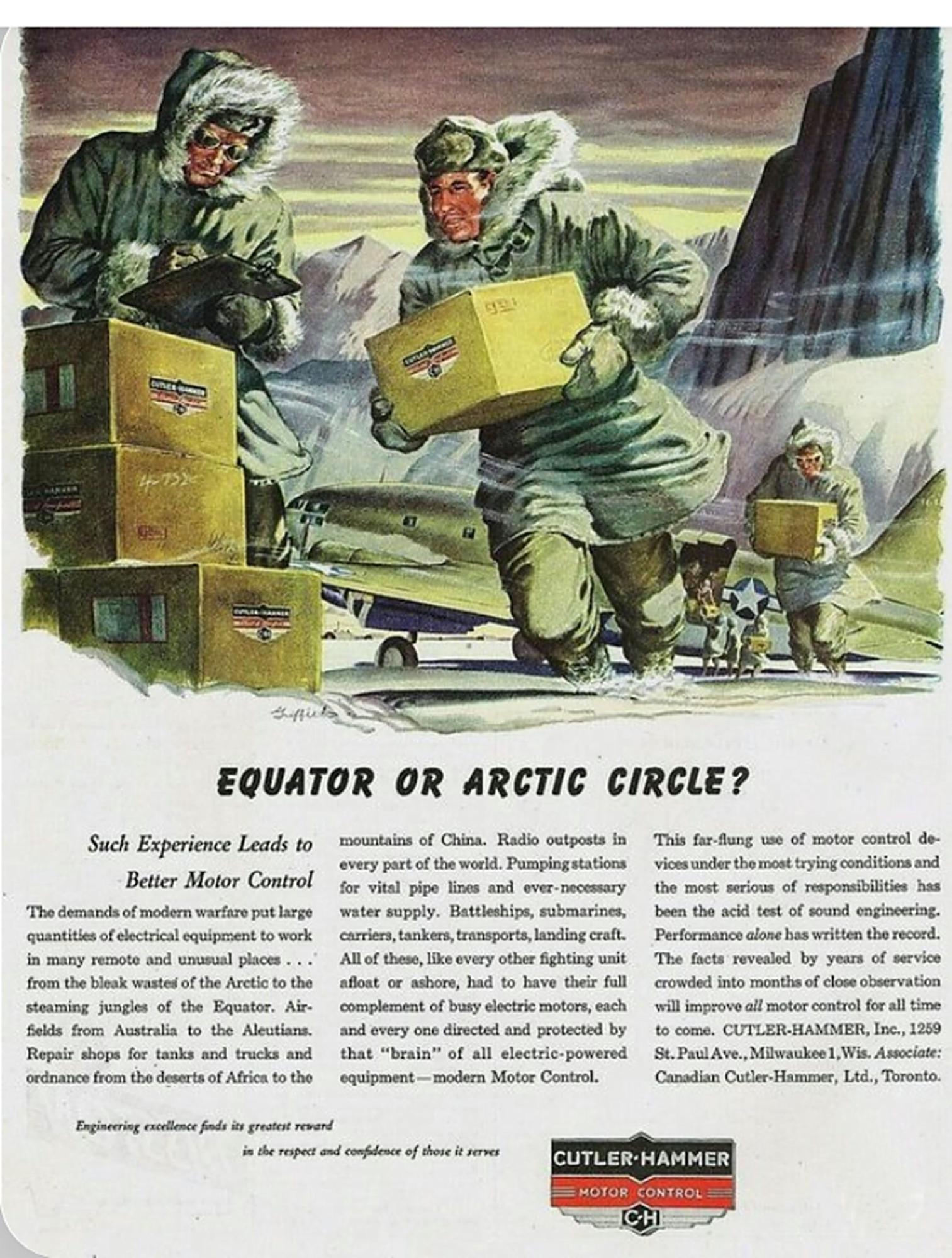

The Navy accepted the offer and Cutler-Hammer’s plants converted operations to production for the military, and for factories producing materials for the war. Orders poured in, taxing the company’s capacity. Cutler-Hammer rented a number of other facilities in the Milwaukee area to meet demand. It is reported that they increased floorspace by 200,000 square feet almost overnight, and hired more than sixty subcontractors to supplement the effort. The plants ran around the clock, seven days a week and employment grew to almost 8,500. Many women were hired to replace the over 3,000 company employees that enlisted in the military.

The list of electrical products that Cutler-Hammer produced during the war is extensive. It included switches for military planes—the B-29 had seventy Cutler-Hammer switches which controlled the 28-kWs of electrical energy used for various motorized control purposes onboard the airplane, such as bomb release and electrical machine gun switches, retractable landing gear and wing flap controls, complete airplane lighting controls, and switches for its fuel pumps.

The company also made motor controls for numerous factories, for the Country’s defense industries.

While Cutler-Hammer produced control devices for every branch of the military during World War II, it’s controls for Naval vessels were particularly significant.

For submarines, the company made controls for the main propulsion and auxiliary motors, as well as for the steering gears, ballast pumps, and elevating gears that guided them. It also made controls for things like vent fans, fresh and salt-water pumps, periscope hoists, and anchor windlasses. Similarly, the company outfitted battleships and cruisers with controls for hundreds of applications.

Under wartime conditions, problems surfaced. The initial controls by Cutler-Hammer and other companies for Navy and merchant marine vessels were modifications of standard motor control equipment. The materials were upgraded for use in a salty environment, but functionally they were the same.

The motor controls could misfunction when shocked by the thunderous jolts resulting from enemy fire. Shells and torpedoes exploding in the water near the vessels caused brutal shock waves to impact the ship, affecting all mechanical equipment. Some controls that should have been off were jostled into the on position, and vice versa. This could cause a near miss to temporarily disable a warship or submarine and leave it vulnerable to a direct hit.

Cutler-Hammer was tasked by the Navy to make its motor controls shock resistant. With no data to work with, its engineers employed a technique used in England in which the motor control was affixed to a metal plate that was struck with a weighted pendulum. The weight and arc of the pendulum provided a measure of the impact force, and high-speed photography was used to determine what happened inside the controllers.

Based upon these impact tests, the controllers were redesigned and tested, and eventually designs were incorporated that would withstand the shock waves that could occur during battle conditions. Cutler-Hammer’s quick response to the situation reinforced the company’s position as a preferred supplier to the Navy.

Demand for electrical equipment remained strong throughout the war but fell off sharply during the latter half of 1945. Once the United States achieved victory over Japan, the majority of remaining military contracts were canceled with negotiated termination.

Cutler-Hammer shifted back to commercial products for the strong demand that occurred during the post-war years, although the shift took it longer since it had moved completely out of the market during the war years.

Cutler-Hammer was purchased by the Eaton Corporation in 1978. Controls for the US Navy continue to be manufactured in Milwaukee by Leonardo DRS Naval Power Systems, which acquired this line of business from Eaton Corporation. The facility works on advanced power systems for Naval vessels.

In 1901, Milwaukeean Thomas Watson acquired a small former shoe factory located on Hannover Street (today’s 3rd Street) in Milwaukee’s Walker’s Point and established the Mechanical Appliance Company. In spite of its name, Watson’s intention was to make electric motors.

His cousin, Louis Allis, became interested as well. Louis had left his father’s company, the Edward P. Allis Company, because of ill health. But, as his health improved, he began to explore investment and employment opportunities. He invested in his cousin’s firm and, in 1903, was elected its president. Watson, an electrical engineer, concentrated on engineering the company’s line of direct-current electric motors.

The timing was good for the company. The availability of distributed electric power was transforming manufacturing processes. Electricity allowed manufacturing factories to locate electric motors where needed to drive machinery. It eliminated the requirement to power all machinery from cumbersome line-shafts and belts.

The company initially manufactured small electric motors and dynamos ranging in size from 1/8th to two horsepower. In 1908, the young firm brought out its first alternating current electric motor. All motors displayed the Watson name.

Importantly, Watson also led the team of engineers that went into factories and assisted in their conversion from line-shaft power to electric motors.

The company quickly outgrew its original manufacturing facility and relocated to Bay View in 1906—on the site of the Allis family’s homestead farm.

In 1922, the company officially changed its name to “The Louis Allis Company.” The company also came out with a series of multi-speed squirrel cage motors in that same year.

For a time, Louis Allis also manufactured exhaust and ventilating fans—all presumably driven by its own electric motors. However, the company eventually settled on exclusively producing specialty electric motors.

In the 1940s the company designed and produced the world’s first integral-horsepower, explosion-proof electric motors. Because of this design, they manufactured almost all of the motors used to drive gun turrets for the United States Navy during the Second World War. The Navy preferred Louis Allis’s steel motor casings since they wouldn’t send out shrapnel if hit by enemy fire, as cast iron-encased electric motors were prone to do.

Eventually, Louis Allis moved operations to Birmingham Alabama, where the company continues to manufacture a full line of electric motors.

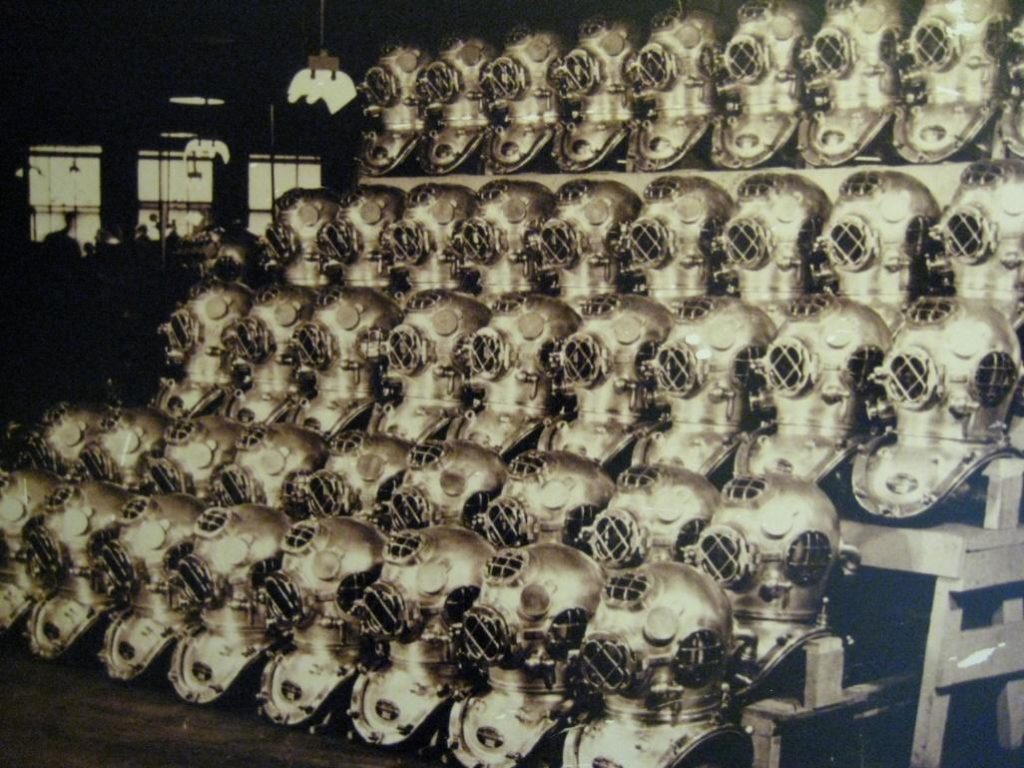

The Diving Equipment and Salvage Company was established in 1937—it is better known by its acronym, DESCO. The company was founded by two Milwaukeeans—divers Max Eugene Nohl and Jack Browne—with the financial backing of Norman Kuehn and the technical assistance of Edgar End, M.D. of the Marquette University School of Medicine.

Max Nohl was known nationally as a skilled diver. Born in Milwaukee in 1910, he obtained his initial diving skills in Lake Michigan. Supplementing these skills with a degree in engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Nohl became the principal diver for an exploration of the South Sea Islands, which was chronicled weekly on a popular national radio show. He also served for a time on a team assembled by a Hollywood producer who was interested in a deep-dive salvage of the Lusitania, the Cunard liner that had been torpedoed by Germany during the First World War. In exploring the possibility of a dive at that depth, Nohl teamed up fellow diver Jack Brown of Milwaukee and Dr. Edgar End, who was a pioneer in studying hyperbaric physiology and medicine.

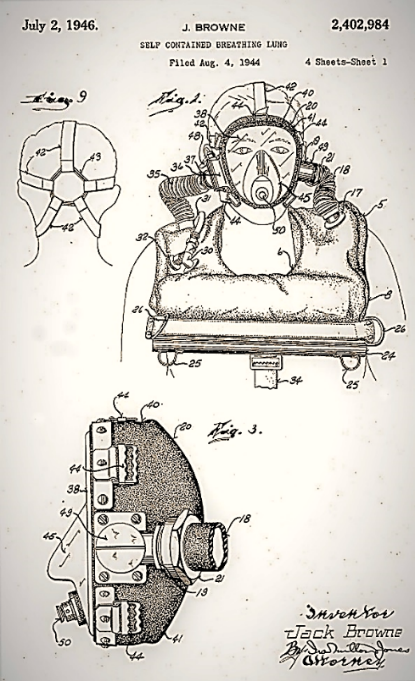

Nohl had already been working on a suit design based on his MIT thesis. Browne and Nohl collaborated on the design of a new lightweight, self-contained diving suit. They also contacted Edgar End about his pioneer work with a helium-oxygen mixture (dubbed ‘Heliox’) to minimize the problems associated with nitrogen narcosis and decompression sickness (the ‘bends’ or caisson disease). End had recently developed decompression tables for the Heliox gas.

Nohl and Browne established DESCO to manufacture the newly designed diving equipment. Norman L. Kuehn, a Milwaukee businessman, provided financing. The company initially operated out of the rear of Kuehn’s Rubber Company’s building at 1053 North 4th Street but moved several times before locating at its current address on North Milwaukee Street.

In a demonstration dive on December 1, 1937, in Lake Michigan, Max Nohl used the newly designed equipment and a helium-oxygen mixture to dive to a depth of four hundred and twenty feet, breaking a record that had previously been set in 1915 by the US Navy diver Frank Crilley.

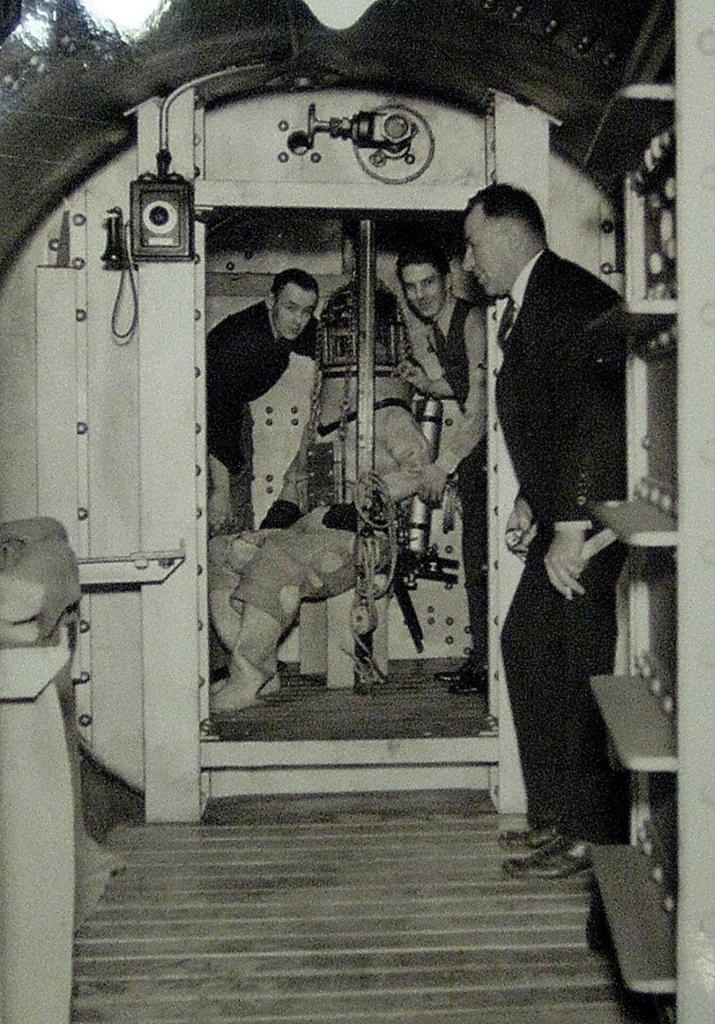

Toward the end of the war, DESCO installed its own pressurized wet tank for research and development. In April of 1945, Jack Browne used this tank to simulate a dive to a new record depth of five hundred and fifty feet of seawater, using a US Navy Lightweight Diving Suit—known as a “Bunny Suit” and breathing a Heliox mixture under the supervision of Dr. Edgar End. The dive is considered a milestone in the development of modern diving techniques.

The development of the self-contained breathing lung—which eventually became referred to as SCUBA gear for “self-contained underwater breathing apparatus”—was an important contribution to diving by DESCO. It was developed five years before the famed Aqua-Lung was introduced in France by engineer Émile Gagnan and Naval Lieutenant Jacques Cousteau. The Cousteau/Gagnon open circuit SCUBA technology was eventually universally adopted and the DESCO rebreather fell out of favor.

The Journal of Diving History describes Max Gene Nohl and Jack Browne as among “American’s most innovative divers. Their working relationship during the 1930s created equipment, broke records, furthered deep-diving technology, and created DESCO. (Browne’s) development of scuba diving equipment … was one of his greatest contributions.”

Following the war, Norman Kuehn and Jack Browne sold the company to Milwaukee businessman Alfred Dorst. In 1967, Thomas and Marilyn Fifield purchased DESCO and moved the company to its present address at 240 North Milwaukee Street in Milwaukee.

Tom Fehring has written extensively about Milwaukee-area industry, highlighting innovation that resulted in the formation of numerous companies that employed hundreds of thousands of Milwaukeeans. His latest book, entitled “The Magnificent Machines of Milwaukee,” is available for sale at the Milwaukee County Historical Society, Historic Milwaukee, Boswell Books, and on Amazon.com.

Memorial Day to Labor Day

8AM-8PM daily

Labor Day to Memorial Day

8AM-6PM daily