This is the fourth in a series of articles that highlight contributions of Milwaukee-area industry to the war effort during World War II. Many thousands of Milwaukeeans, men and women, helped to provide the munitions and other products that made Victory possible.

Earlier articles in this series chronicled the activities during the Second World War of Milwaukee companies Allis-Chalmers, A.O. Smith and South Milwaukee’s Bucyrus-Erie. These three companies were far from alone in contributing to the war effort. Louis Allis, Badger Meter, Briggs & Stratton, Chain-Belt, Cleaver Brooks, Cutler-Hammer, DESCO, Evinrude, Falk, Filer & Stowell, Globe Union, Harley-Davidson, Harnischfeger, Heil, Kearney & Trecker, Johnson Controls, Ladish, Milwaukee Tool, Nash, Nordberg, Square D, Vilter, Waukesha Motors, and David White are just a few of the dozens of Milwaukee-area companies that provided the United States and its allies with the munitions, equipment, and supplies for the war effort. Collectively, they were part of America’s ‘Arsenal of Democracy.’ They helped achieve Victory in Europe and Victory Over Japan.

This article discusses the important contributions of just a few of the above companies that manufactured bullets, fuses, and other military products during the war.

Several Milwaukee industrial companies stepped up to produce fuses during the War, including Badger Meter, Evinrude, and the Centralab Division of Globe Union.

Centralab’s proximity fuses were particularly innovative. Their fuses used a special radar sensor to detect the proximity of the target and to explode just prior to impact in order to cause the most damage.

The printed circuit board they used in their fuse was a closely-held secret of the United States and allowed the device to be small enough to mount on the head of a mortar shell.

It was a difficult engineering feat because the circuits had to withstand the incredible force of being fired from a cannon. The fuses also needed to be produced quickly and in quantity. Centralab met the requirements by employing a ceramic plate that was screen-printed with metallic paint for conductors, and used a carbon material for the resistors. Ceramic disc capacitors and subminiature vacuum tubes were soldered in place. This circuit design, which eventually became known as a thick-film hybrid circuit, was successful. Armaments equipped with these proximity fuses were critical during the Battle of the Bulge, as well as during engagements on the Pacific Front.

A patent for the technology was assigned to Globe-Union, but was classified by the US Army. Many years later the Institute of Electric and Electronics Engineers awarded Harry W. Rubinstein, the former head of the Centralab Division, its Cledo Brunetti Award for early key contributions in the development of printed circuit boards.

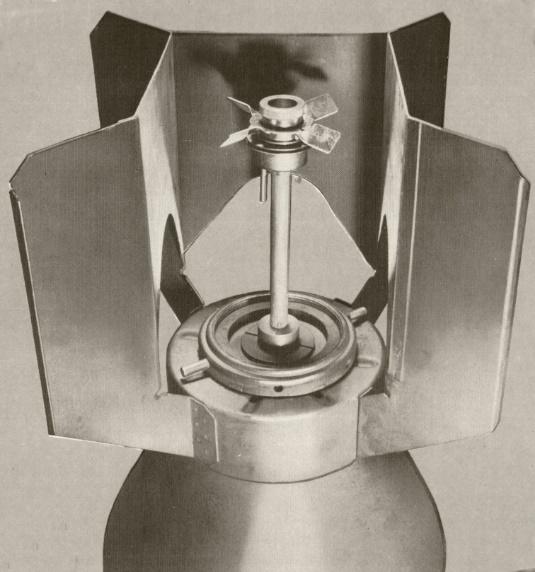

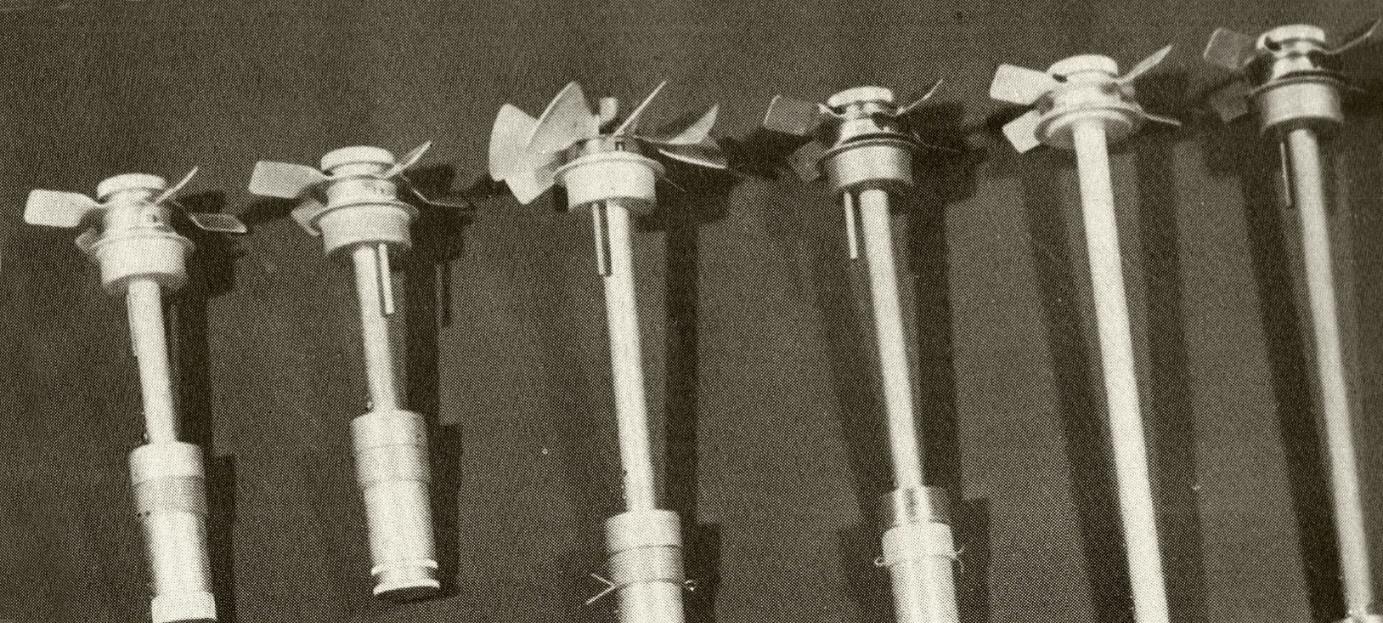

The equipment and skills that Badger Meter had developed for producing water and other fluid meters turned out to be perfect matches for manufacturing bomb fuses. In early 1942, Badger Meter received an initial order for 200,000 fuses. Badger produced both nose and tail fuses. The tail fuses generally carried a small propeller. As the bomb descends, the propeller begins to turn and, in the process, arms the firing pin. When the bomb strikes its target, the firing pin strikes a cap, which sets off the primer charge and initiates the explosion.

In order to meet the production targets established by the War Department, fuse production accounted for ninety-five percent of Badger’s total output. By the end of 1942, the company’s employment doubled to five hundred and fifty—many of which were women.

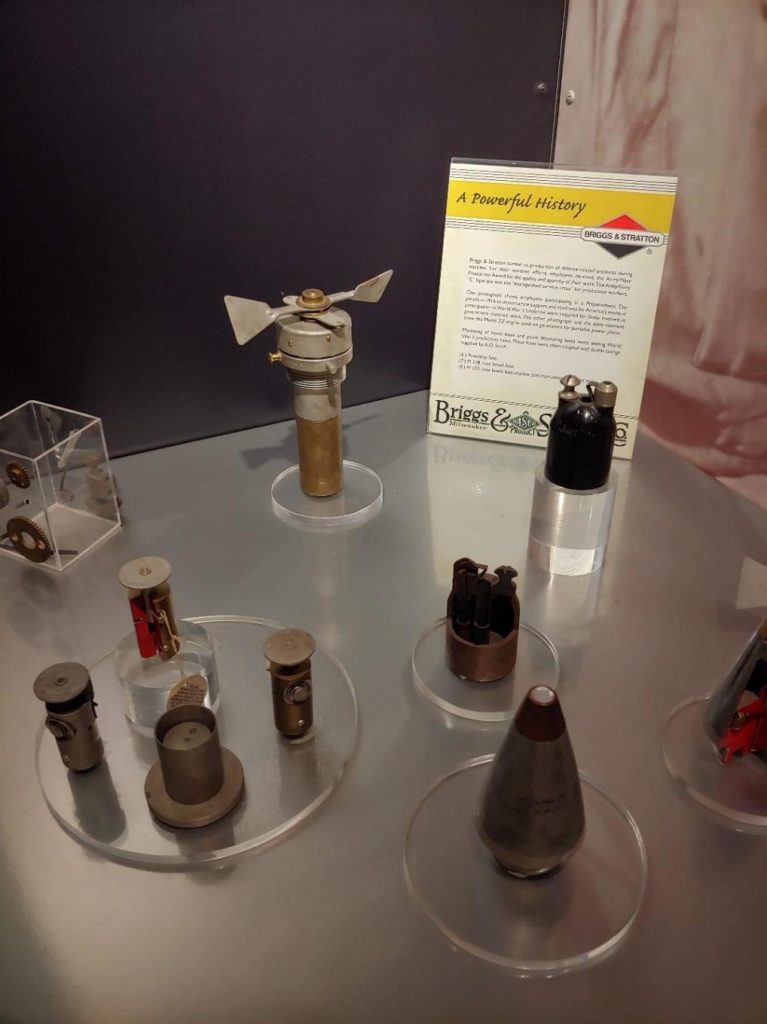

Briggs & Stratton’s initial foray into wartime production also involved fuses, in particular, fuse caps for use in aerial bombs and artillery shells. As the war progressed, they also began production of electrical switches for aircraft, including trainers, fighters, and bombers. They also introduced a magneto for airplane engines designed to work in the extreme cold temperatures at altitudes above 35,000 feet. Briggs & Stratton magnetos were used on the P-47 ‘Thunderbolt,’ the P-61 ‘Black Widow’ and the A-26 ‘Invader.’

Milwaukee’s Evinrude also converted its manufacturing facilities to the production of war materials. Bomb fuses, aircraft engines, and firefighting apparatus flowed from their factories. Evinrude also produced outboard motors for the Navy—more will be reported on that in the next installment.

In 1942, United States Rubber Company obtained a federal contract to produce .50-calibre machine gun ammunition. In order to get up and running quickly, they selected a vacant factory in Glendale Wisconsin, which had been built by the Uihlein family (Schlitz) during the depression for its Eline Candy Company. The factory was located on North Port Washington Road just south of Hampton Road. The new enterprise was named the Milwaukee Ordnance Plant. Five thousand employers were hired to operate the facility around the clock, six days a week.

Operations ramped up quickly and eventually the facility shipped up to 28 railroad boxcar-loads of cartridges each week. In a September 29, 1943 story about the factory, the Milwaukee Journal oddly reported that enough “cartridges have been made at the plant to kill everyone in the United States.”

In fact, production was so high that the supply of ammunition soon exceeded the needs of the Allied forces during the war. In a newspaper article the following month, the Journal reported the Milwaukee Ordnance Plant had shut down, having “turned out more .50 machine gun ammunition than all the plants in the county turned out in World War I. It is good ammunition. It is stacked high in this country and near all fronts and future fronts.” The article went on to note that “It was a costly year. A big job had to be done in a hurry. It was part of the necessary extravagance of war—for war is waste, at best.”

In his book entitled Lost Milwaukee, historian Carl Swanson reports that the Army assigned Col. Arthur M. Wolff to oversee operations. Wolff formerly was a member of the board of directors of the Institution for the Improved Instruction of Deaf Mutes in New York. He made it a point to recommend hiring women who were hearing disabled to work at the Milwaukee Ordnance plant.

Wolff believed hearing impaired women made ideal employees. As he related to a local newspaper, “Noise does not distract them. There is never any idle conversation, and they generally have the steel will to succeed on the job with steady and hard work.”

Forty-one billion rounds of ammunition were produced by the Allies during the Second World War—a sizable portion of which was produced at the Milwaukee Ordnance Plant.

As the above oft repeated phrase implies, it is imperative that military forces be well-provisioned. Without fuel, aircraft, tanks, trucks and ships come to a halt. And without food, solders will eventually become unable to function. To this end, Milwaukee’s J.W. Speaker Co.’s products were essential to the war effort.

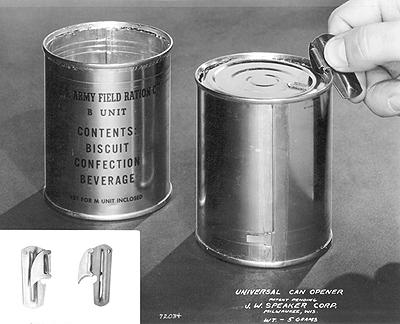

The company was formed in 1935 to produce various automobile accessories, including tire repair kits, radiator fronts, car and truck mirrors and automobile lights. However, during the war, J.W. Speaker turned its production to military uses. Both of its products were related to feeding the Allied troops—simple tools that assisted soldiers in the field.

The most recognized product was the ‘P-38’ can opener. The device was commonly included in meal rations, to assist in opening the sealed cans. Speaker was among the first to produce this ubiquitous product. The company produced some fifty-million of the can openers between 1942 and the 1970s.

The P-38 was not initially developed by J.W. Speaker, but he provided a significant innovation to improve it. The original opener blade was prone to open by itself, which could cause cuts or rip holes in clothing. The Army explained the problem to John W. Speaker and asked if he could solve it. Speaker, who had studied engineering in Austria before immigrating to the United States in the 1920s, made a slight modification—he added what he referred to as a ‘detent’ in which two extensions on the opposite side of the hinge mechanism kept the cutting edge shut when not in use. It was a simple and inexpensive fix, for which he was awarded a patent, but allowed the design to be used by other manufacturers to aid in the war effort.

The company’s other device for military use was the Heatab miniature portable stove. It was a simple stand that was designed to suspend a container of food above a heating platform. The kit included a dry fuel disk that could be easily ignited with a match. Its small size enabled it to be easily carried, and its use must have provided a welcome warm meal during adverse field conditions.

The David White Company started

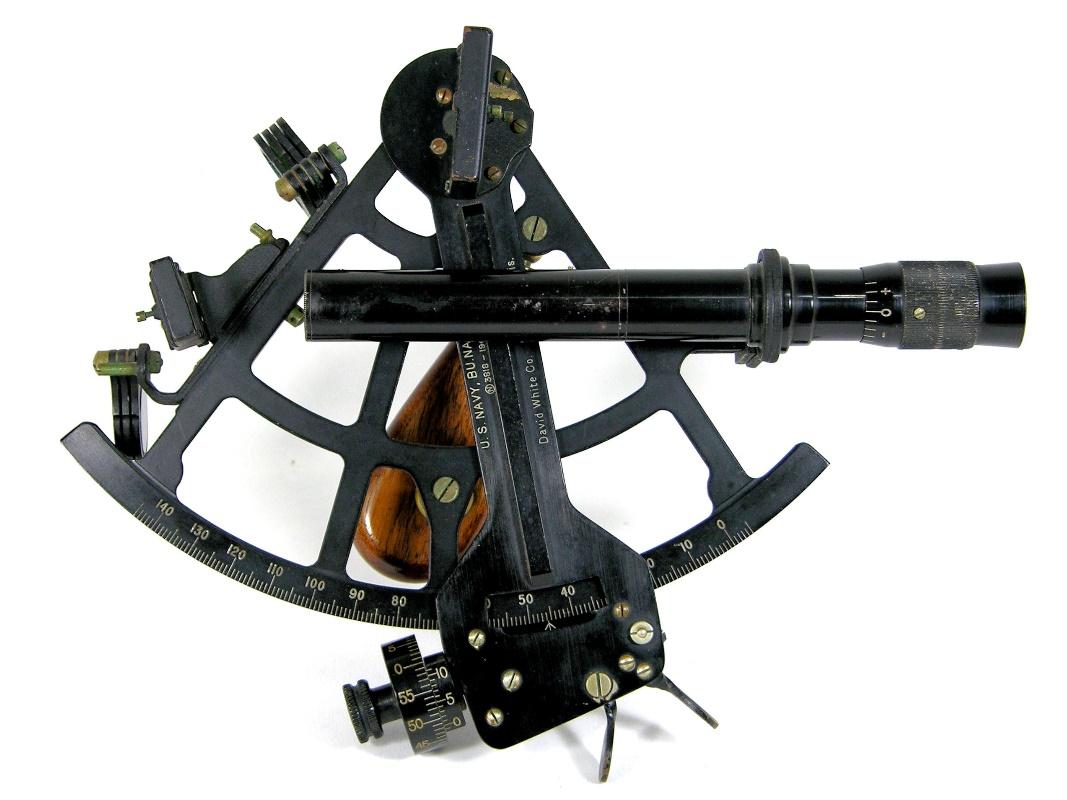

During the Second World War, David White Company produced navigation instruments for the United States Navy. The company produced a quintant—similar to a sextant but the instrument’s arc covered 1/5th of a circle. The use of a mirror on the index arm multiples this by two and makes it especially useful in celestial navigation by lunar distances. The quintant was the last significant development for nautical navigation before the introduction of electronic navigation and global positioning systems.

Tom Fehring has written extensively about Milwaukee-area industry, highlighting innovation that resulted in the formation of numerous companies that employed hundreds of thousands of Milwaukeeans. His latest book, entitled “The Magnificent Machines of Milwaukee,” is available for sale at the Milwaukee County Historical Society, Historic Milwaukee, Boswell Books, and on Amazon.com.