This is the second of a series of articles that highlight contributions of Milwaukee-area industry to the war effort during World War II. Many thousands of Milwaukeeans, men and women, helped to provide the munitions and other products to make victory possible.

For most Milwaukee-area companies, contributions to the war effort involved much more than the manufacture of weapons and ammunition. Not only did the United States and Allied military forces need to be armed, they also needed to be fed, provided with transportation, and supplied with fuel for their aircraft, naval vessels and trucks, along with all of the other necessities to sustain them. At the same time, factories needed to be supplied with steel and other metals, fuel, electricity and other essential products.

As an example, Milwaukee’s A.O. Smith Corporation contributions to the war effort began well before the United States was actively engaged in World War II. Established in 1874 as C.J. Smith and Sons as a producer of parts for buggies and bicycles, A.O. Smith developed a particular expertise for forming steel parts into automobile and truck frames, and into pipe and other products. It also became known for its advanced welding techniques.

During World War I, A.O. Smith received orders for various war materials including caisson wheel hub flanges, frames for Army trucks, and casings for bombs. It had challenges in producing casings for the 100-pound bombs — the largest bombs being produced for aircraft at the time. Welding the casings with oxyacetylene gas flame produced a fairly crude weld, and there was an acute shortage of oxyacetylene during the war. A.O. Smith was familiar with arc welding using a coated weld rod imported from England. The coated welding rod, called the Quasi-Arc weld rod, was coated with asbestos to resist the heat of the arc, allowing an ionized atmosphere to be produced at the welding tip capable of producing welds of reasonable metal properties. However, German submarine activity precluded shipping the weld rods to the United States.

A.O. Smith turned to its engineers to find a suitable substitute. After a month of experimenting, a team led by Reuben Stanley Smith which included Orrin Andrus and Dick Stresau, developed a welding rod with a coating of paper pump and sodium silicate, both of which were inexpensive and readily available. The resulting weld rod was cleaner, simpler, swifter and more accurate in temperature control than gas-flame welding. It also avoided the use of asbestos. The Smith weld rod launched the company into the business of producing weld rods and it became recognized as a pioneer in electric arc welding, as well as other welding techniques.

In 1927, the company introduced resistance flash welding; a type of resistance welding that does not require a filler metal. The welding process involves setting the pieces of metal to be welded at a predetermined distance. Current is then applied and an arc is produced across the gap. Once the pieces of metal reach the proper temperature, they are joined, effectively forging the pieces together. A.O. Smith applied the technology to produce longitudinal pipe joints. After the joint was formed and any surplus metal removed, an internal mandrel was run through the pipe, which rounded the pipe to its final dimension, and tested the pipe at the same time. The highly productive process was capable of manufacturing longitudinal seams of 40-foot lengths of large-diameter pipe in 30 seconds.

A.O. Smith soon began using the above welding techniques for the production of pipe for the petroleum industry. Prior to this innovation, piping was manufactured from solid cast billets that had to be reamed, drawn and straightened into the desired dimensions—a costly and time-consuming process. A.O. Smith was able to roll sheets of steel into pipe with welded longitudinal joints. Soon the company was producing up to thirty-five miles of oil pipe per day, supplying most of the oil pipeline industry’s requirements.

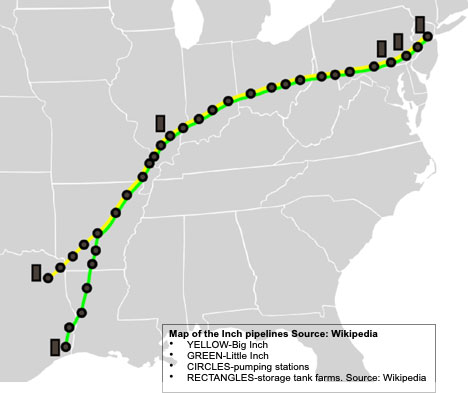

A.O. Smith’s welding capability came into play prior to the United States’ involvement in World War II. Petroleum products were commonly transported from the oil fields of Texas to refineries in the northeastern United States via oil tankers. When the Second World War broke out in Europe, German U-boat submarines threatened this link. To protect this vital resource, two underground pipeline projects were approved as emergency war measures. Constructed between 1942 and 1944, the Big Inch and Little Big Inch pipelines were 1,254 miles and 1,475 miles long respectively, with 35 pumping stations along their routes. The project required 16,000 people and 725,000 tons of materials — most of which was large diameter steel piping. A.O. Smith was one of the principal pipeline suppliers. Crosstown Milwaukee manufacturer Allis-Chalmers provided most of the pumps for the pipelines.

In the Fall of 1942, eight pipe laying crews, each consisting of between 300 and 400 men, began working in the field to install the underground pipe. The schedule called for five miles of the Big Inch pipeline to be installed each day, a rate which was eventually almost doubled. During the project, approximately 7,000,000 cubic yards of material were excavated. The first ‘leg’ of the Big Inch line, between Texas and Illinois, was placed in service on New Year’s Eve 1942. Work on the Little Big Inch then began in 1943.

The pipeline project was considered one of the greatest engineering feats of the war.

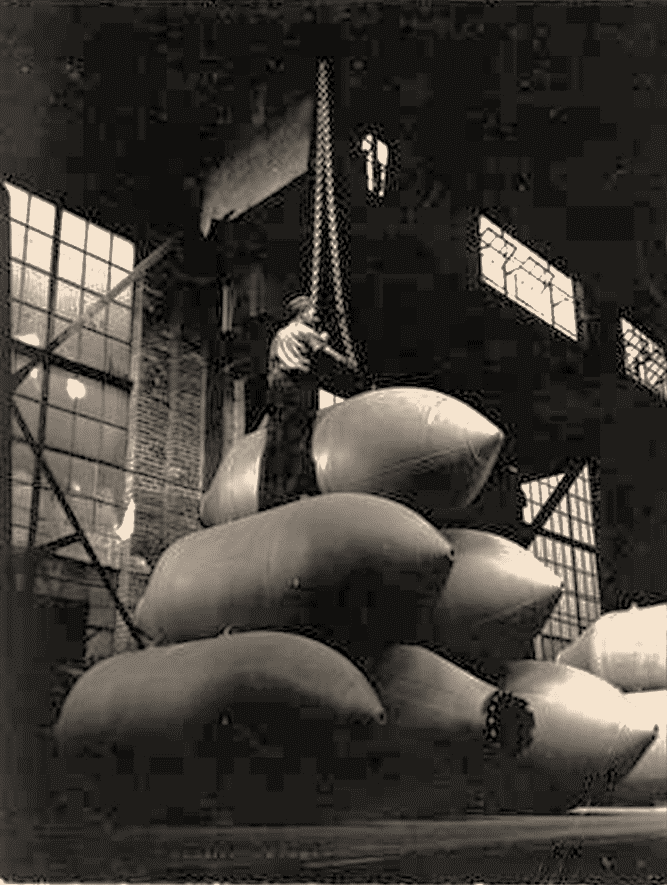

When the United States entered into WWII, A.O. Smith was again called to produce bomb casings—this time in the “blockbuster” class—ten times the size of the bombs it produced for the prior war. The nose and base of the bomb were manufactured using forging hammers of the company’s own design. The sides were produced using ordinary steel tubing—all assembled with arc welding. The resulting design reduced cost and allowed the company to produce a thousand of the biggest bombs in a single day.

Because of its welding expertise, A.O. Smith was consulted by William (Bill) Knudsen during the war about using welding techniques, rather than riveting, to construct the Liberty ships. Knudsen, who oversaw the nation’s manufacturing companies in providing material for the war effort, inquired whether it would be feasible to weld the thick steel plate for the ships since doing so would greatly increase productivity. Based in part on the advice received from the company, Knudsen directed that the Liberty ships use new welding techniques. Rudolph Furrer of A.O. Smith was assigned by the company to the U.S. War Metallurgy Committee to advise the Army on ordinance research and development, where he contributed to the design of the Liberty ships and tanks, and for the casings for the atomic bombs. Furrer was posthumously inducted into the Army Ordnance Hall of Fame in 1993 because of his contributions to the war effort.

The decision to produce the Liberty-class ships, and later the Victory ships, using modern welding techniques allowed the United States to build over 3,200 of these ships during the course of the war. The first ships required about 230 days to build, but the average eventually dropped to an amazing 42 days, using welding and mass production techniques.

During WWII, A.O. Smith also produced, aircraft propellers and landing gear, torpedo air flasks, and other materials to support the Allies. By 1945, the company had built 4.5 million bombs, 16,750 sets of landing gear, and 46,700 propeller blades, as well as nose frames for the B-25 bomber, water heaters, jeep frames, and components for the atomic bomb project (1942-45).

Tom Fehring has written extensively about Milwaukee-area industry, highlighting innovation that resulted in the formation of numerous companies that employed hundreds of thousands of Milwaukeeans. His latest book, entitled “The Magnificent Machines of Milwaukee,” is available for sale at the Milwaukee County Historical Society, Historic Milwaukee, Boswell Books, and on Amazon.com.