This is the ninth in a series of articles that highlight contributions of Milwaukee-area industry to the war effort during World War II. Many thousands of Milwaukeeans, men and women, helped to create the munitions and other products to make Victory possible.

President Franklin Roosevelt stated in July 1943, “Every combat division, every naval task force, every squadron of fighting planes is dependent for its equipment and ammunition and fuel and food . . . on the American people in civilian clothes in the offices and in the factories and on the farms at home.” This was certainly true in Milwaukee, which was one of the principal centers of manufacturing in the country. The factory workers who helped to create the munitions of war and to supply the United States armed forces were a central part of the war effort. They can be credited for helping to achieve victory in Europe and victory over Japan. The effort went well beyond factory work. Other Milwaukee area workers continued to produce essential goods and services that were critical to sustaining the United States. Farmers supplied the food necessary to sustain the country, as well as its soldiers; streetcar operators ensured people got to work; teachers prepared the city’s children to become educated citizens; and telephone operators and postal employees worked to staff the phones and deliver the mail. The list goes on and on of people who performed critical activities throughout the war years. Few households were untouched by the war. The millions that were recruited or drafted into the military left many families temporarily without husbands, fathers, sons and daughters. One out of every five American families had someone serving in the military—some more than one. Four hundred thousand of these men and women did not come back—their families usually displaying gold star service flags in their windows. At the time, the Allis-Chalmers facility Roosevelt toured was manufacturing a variety of materiel for the war including steam turbines for ships, submarine motors, generators, and electrical switch gears.

Many Milwaukeeans volunteered in various activities to support the war effort. Civilians rolled bandages for the Red Cross, entertained servicemen and women at USO canteens, collected scrap metal and other materials, and assisted in selling bonds. Some worked at the USO, or with the Salvation Army, the Knights of Columbus and the Boy Scouts to meet servicemen and their families passing through railway stations and providing them with sandwiches and reading material. Other volunteers served on advisory boards created by federal agencies to help manage, explain, and support government programs for civil defense, war bond sales, rationing, and price control.

On September 16, 1940, the United States passed the Selective Training and Service Act, requiring all men between 21 and 45 to register for the draft. This was the first peacetime draft in the history of the country.

Initially the draft did not apply to married men. This resulted in a temporary increase in marriages. However, soon married men without children were drafted, and eventually fathers became eligible for the draft in late 1943. Between October 1943 until December 1945, nearly a million fathers were drafted.

Essential employees in industry and agriculture were exempted from the draft. During the course of the war, about four million men received deferments for essential occupations. However, many chose to go anyway—most for patriotic reasons.

Farm employment suffered as men joined the services and farm hands left to take up better paying jobs in the factories. The shortage of farmworkers made it difficult to plant, grow and harvest crops. In 1942, a shortage of workers resulted in some crops left unharvested. Given the increased need for food to feed both normal domestic requirement plus the added needs of the military, the United States Agricultural Department stepped in. The department created the United States Crop Corps to enlist women and young teens to take up work on farms. Approximately 1.5 million women and 2.5 million teens joined the Crop Corps during the war. They played a vital role in ensuring that the nation and its soldiers were fed.

As manufacturing needs increased and the pool of available employees decreased, employers turned to the elderly and young. Some working men that had been classified as unfit for health reasons took second jobs. The unemployment rate dropped as low as 1.2 percent during the war—essentially everyone was working, yet the demand for employees was unsatisfied.

Industry had no choice but to recruit other workers to meet their needs. They turned to women, and eventually African Americans and Mexican Americans.

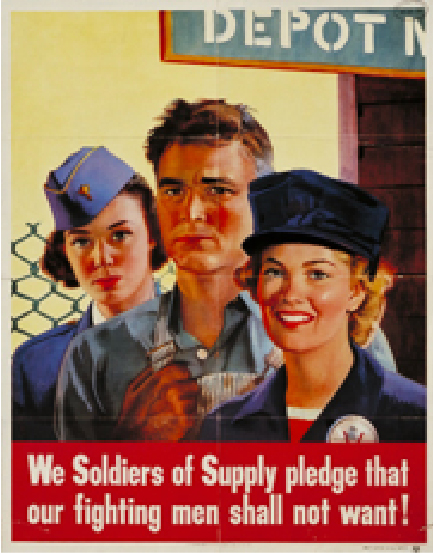

Initially the government discouraged the hiring of women until all unemployed men were employed. During the Great Depression, the public was generally hostile to hiring women while so many men were unable to find employment. But with essentially full employment of able-bodied men, a national campaign was initiated to encourage women to enter the workforce—and to encourage manufacturers to employ them.

More than six million women joined the workforce. The image of ‘Rosie the Riveter’ came to symbolize the wartime experience, suggesting that the roles for women in manufacturing had expanded into non-traditional jobs. The reality was a bit more nuanced, as historian David Kennedy has written. Though women filled a much greater array of industrial jobs, they were more likely to be in lesser-skilled roles. According to his analysis, the longer-lasting employment gains were made in white-collar secretarial, clerical, and sales jobs than in factory work.

The reality in Milwaukee is that women filled numerous critical manufacturing roles throughout the war.

One consequence of the war was that the ‘marriage bar’ that had previously prevented married women from working in industry was largely eliminated, especially for women with older children. By the time the war ended in 1945, the majority of women in the labor force were married and over 35—constituting a majority of female labor for the first time.

There was also a shift of women from domestic jobs to better paying industrial jobs.

While the strides for women during the war were significant, the general expectation was that women were holding the jobs only ‘for the duration.’ Indeed, once the war was over, the majority of younger women left the workforce. Many of them soon married and began raising families. Two years after the war, the percentage of women employed was about thirty percent—which was in-line with long-term trends.

However, the experience of the women who entered the workforce during the war years led to some significant changes to society. Mary Anderson, who was head of the Women’s Bureau of the Department of Labor stated, “Almost overnight women were reclassified by industrialists from a marginal to a basic labor supply for munitions making.” Even as the men returned home from the war and assumed the jobs formerly held by women, society’s acceptance of women in non-traditional roles had begun to change.

At the height of the war, there were 19,170,000 women in the labor force, an increase of 6.5 million or over 50 percent. They represented approximately 35 percent of the civilian workforce. Women comprised four percent of skilled workers, who made an average weekly wage of $31.21—less than 60 percent of what their male counterparts were paid.

In addition to typically earning far less than their male counterparts, women employees often faced harassment and discrimination in the workplace. Still, most women appear to have had favorable impressions of the experience—many sought to remain in their jobs. Those who were able to retain employment were often demoted as the men returned home.

As noted, in order to fill jobs employers typically turned first to married fathers, those with deferments because of critical skills or disabilities, to the young and elderly, and then to women—all before hiring African Americans.

The March on Washington Movement led by A. Philip Randolph with allies from the NAACP and other civil rights organizations, placed pressure upon president Franklin D. Roosevelt to establish policies against employment discrimination. When Roosevelt issued an executive order that prohibited discrimination in the defense industry under contract to federal agencies in 1941, Randolph and his collaborators called-off a planned protest march. He did, however, continue to fight for employment fairness throughout the war.

Roosevelt established a Fair Employment Practices Committee to combat discrimination against blacks as well as other ethnic groups, and encourage employers to hire them. However, the gains in employment likely came as much from the need for willing and able workers, as they did from government policy.

Many African Americans, encountered hostility and prejudice on the job, despite the work of the government’s Fair Employment Practices Committee. White workers occasionally staged strikes to protest the hiring or promotion of African Americans.

The government continued to practice strict segregation in the military, as well as in government housing. Some white ethnic groups, often living in crowded conditions themselves, protested when African Americans were granted government housing.

The war did result in significant gains for African Americans. They held only three percent of defense jobs prior to the war, but more than eight percent by its conclusion. While this was less than their ten percent of the population, it was a considerable gain. As the numbers of African Americans in manufacturing increased, more were employed as foremen and craftsmen.

While the gains during the war reduced the gap between the economic status of whites and blacks, black median income was only about half that of whites at the end of the war. Furthermore, African Americans were unable to make inroads in obtaining professional, managerial, and white-collar jobs.

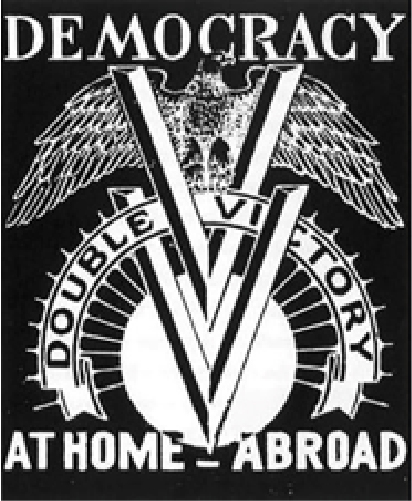

In 1942, James G. Thompson, a young black man, wrote an article for the Pittsburgh Courier entitled, “Should I Sacrifice to Live ‘Half-American?” The newspaper, in response, launched the ‘Double V’ campaign, which called for ‘victory over enemies abroad, and victory over discrimination at home.’ It sparked a conversation that eventually went national.

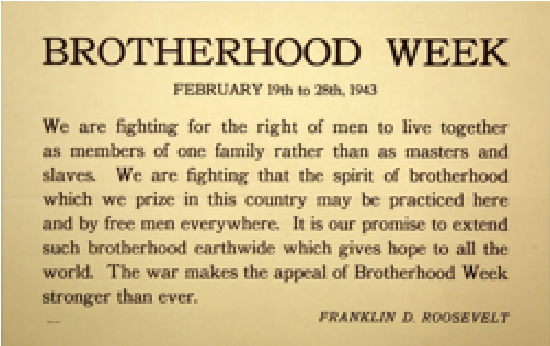

In 1943, the president declared Brotherhood Week that stated, in part, “We are fighting for the right of men to live together as members of one family rather than as maters and slaves.”

In spite of its wartime needs, segregation in the military continued. African American units fought with distinction and led the way to the eventual desegregation of the military—although this did not occur until well after the conclusion of the war.

About one million African Americans served in the armed forces during the war; most in segregated units.

Given that industry was in need of a large number of trained workers during the war, the Milwaukee vocational and adults school system stepped up, in cooperation with the Federal government.

During the war, almost 37,000 workers were trained in courses that were held on a 24-hour schedule. Local companies sent their new employees to learn mathematics, blueprint reading, inspection and testing. Courses were also held in auto and diesel engine mechanics, aircraft mechanics, electricity, foundry, machine shop, sheet metal and welding. Both men and women attended.

As job opportunities opened up in the industrial centers, significant migration occurred. People left rural areas for the cities. African Americans left the rural south to take up jobs in the defense plants in the Northeast and Midwest, as well as the Pacific Coast. Nearly three-quarters of a million African Americans moved during the war. During the 1940s, the proportion of African Americans living in the South declined by almost ten percent, while those living in urban areas rose.

Many military bases were located in Sunbelt states, causing millions of soldiers and their families to relocate—some deciding to stay following the war.

Mobilization also brought important demographic changes. As one example, over 400,000 African American women quit work as domestic servants to assume better paid jobs in industry and elsewhere during WWII.

While often putting in long hours working at difficult jobs, Milwaukee workers gained financially during the war. Those that had suffered during the Depression decade now found themselves in jobs that paid reasonably well. As the saying goes, the tide lifts all ships. Workers from all demographic groups gained. New immigrant groups such as Italian and Polish Americans made economic gains, as did women, African Americans and other workers. In addition to better pay, they were often afforded with better jobs and other opportunities during the war.

Those that served in the military, men and women, black and white, also benefited from the opportunities, training, and experience provided because of their service. Many were helped by medical care benefits, as well as the educational and home-ownership provisions of the G.I. Bill.

While gains were made during the war, labor conflicts did occur. In his book A City at War, Milwaukee historian Richard Pifer focuses on the labor issues that occurred in area industry. He summarizes a number of labor strikes at area industry.

Pifer summarizes the issues that resulted in labor actions and strikes, even as the facilities were turning out needed materials for the ongoing war—a practice that some regarded as disloyal. He concludes that strikes were fewer and of shorter duration during the war than they were outside of war years.

Those that served in the military, men and women, black and white, also benefited from the opportunities, training, and experience provided because of their service. Many were helped by medical care benefits, as well as the educational and home-ownership provisions of the G.I. Bill.

Federal taxes increased significantly during the war, to help pay the enormous costs. Federal tax policy was a highly contentious issue. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the opposing conservative coalition in Congress agreed on the need for high taxes (along with heavy borrowing) to pay for the war, but the details were not easily resolved.

High marginal tax rates were imposed, ranging from 81% to 94%, and the income level subject to the highest rate was lowered from $5 million to $200,000.

Congress lowered the minimum income on which people needed to pay taxes. As a result, by the end of the war nearly every employed person was paying federal income taxes, compared to only about ten percent who paid federal taxes prior to the war.

Other controls were imposed, such as a cap on executive pay for corporations that had government contracts.

The war effort resulted in the shortage of many goods and materials. In order to guarantee minimum necessities for everyone, as well as to provide needed materials for the war, a rationing system was put in place beginning in 1942. Tires were the first item to be rationed, although eventually it became evident that rationing gasoline would also limit the amount of rubber needed. By 1943, ration coupons were required to purchase coffee, sugar, meat, cheese, butter, lard, margarine, canned foods, dried fruits, jam, gasoline, bicycles, fuel oil, clothing, silk or nylon stockings, shoes and many other goods. Automobiles and home appliances were no longer made; used autos were in hot demand. Automobile driving for sightseeing was banned.

Everybody was issued rationing stamps, including children, by local rationing boards. Ration stamps had expiration dates, to prevent hoarding.

Other controls were put on the economy as well. Price controls were imposed on many products by the Office of Price Administration. Wages were also controlled. Corporations involved in the war effort were overseen by government agencies including the War Production Board and the War and Navy Departments.

Baby boom

The war caused millions of Americans to postpone marriage. As servicemen returned from the war, marriages soared. Predictably the birthrate shot up as well—ultimately peaking in the late 1950s. This increase was referred to as the ‘Baby Boom,’ and those born during the era called ‘Baby Boomers.’

Housing availability did not keep up with the expanded families, forcing many newlyweds to live with their parents for a time. The G.I. bill helped to support the construction of new homes.

It was difficult to divorce servicemen during the war, but the number of divorces peaked when they returned.

High marginal tax rates were imposed, ranging from 81% to 94%, and the income level subject to the highest rate was lowered from $5 million to $200,000.

Congress lowered the minimum income on which people needed to pay taxes. As a result, by the end of the war nearly every employed person was paying federal income taxes, compared to only about ten percent who paid federal taxes prior to the war.

Other controls were imposed, such as a cap on executive pay for corporations that had government contracts.

Over three-hundred thousand American soldiers died as a result of combat during World War Two—almost 3,000 from the Milwaukee area. These men, and some women, gave their lives in service to their country and in the pursuit of freedom. Additionally, almost six-hundred thousand suffered non-fatal injuries.

We don’t often think of those who also gave their lives, or suffered injuries, working in the factories, mills and mines during the war. But many such Americans suffered heavy physical losses. More than seventy-five thousand workers died or became totally disabled because of industrial accidents during the war, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. An additional 378,000 Americans experienced a permanent partial disability.

The cause of these deaths and injuries are numerous—lack of safety guards on equipment, inexperienced workers, or just carelessness. Workers were putting in long hours and were often exhausted. The drive to produce the needed war goods on schedule obviously led to some safety short-cuts.

The war resulted in significant and lasting changes. World War Two established the United States as a superpower. By the end of the war, the country was producing nearly half of the world’s goods.

In his book by the same name, Tom Brokaw described the people that lived through the war as the Greatest Generation notes, “They weren’t perfect, noting that they made mistakes.” But during their generation, their work, their achievements and their sacrifices were remarkable.

Milwaukeeans of this era certainly fit this description. Their work and sacrifices helped the country to achieve victory, and helped to establish the most powerful peacetime economy in history.

Tom Fehring has written extensively about Milwaukee-area industry, highlighting innovation that resulted in the formation of numerous companies that employed hundreds of thousands of Milwaukeeans. His latest book, entitled “The Magnificent Machines of Milwaukee,” is available for sale at the Milwaukee County Historical Society, Historic Milwaukee, Boswell Books, and on Amazon.com.